It all started with a job interview. I failed one of the essential criteria quite spectacularly, so much so that I’m surprised they even interviewed me. The criteria was practising Christianity.

I figured I was a fairly Christian person. So I only went to church at Christmas, but in terms of being a ‘good’ person, I thought I did OK. In terms of the job, I blitzed the rest of the criteria. So would skill-set trump spiritual-set?

Not. A. Hope.

Not a pleasant feeling either.

My ego had been pricked. The very essence of what I could do was negated by what I was not.

So, like most scorned women, I took myself off for a long weekend with some pals to drink wine, eat chocolate, bitch and drink some more wine. That’d sooth it.

But despite the venting, I wasn’t soothed. Instead, I experienced a none too subtle spiritual shoving that, no matter how much I dug my heels in, pushed me closer and closer to unpacking everything I thought I knew about spirituality. I’ve blogged about the dream on Mum’s funeral morning that gave me much needed comfort. How I could ignore what was going on right now if I wanted to hold my faith in that sign? I couldn’t have it both ways.

I have experienced too many small miracles in the past to ignore what went on that weekend: The Bible falling off the shelf at my feet at the Great Mackerel Beach communal library – with no one nearby to cause it fall. Or the yacht at Palm Beach, the sail unfurling, emblazoned with the words ‘Mister Christian’. Awaking with Jennifer Warnes’s ‘Song of Bernadette’ playing over and over in my head each morning when I had not heard her music in probably a decade.

So, finally, I surrendered. My conversation with God (3am, bolt upright in bed) went something like this:

Phil: Ok, ok, I’m listening. Enough with the signs and interrupted sleep already. What?

God: Work it out. Sort out your faith.

Phil: Yeah, right. Dreams and signs. Plus my way to Christ and faith is more Mary Magdalene meets Oprah’s Super Soul Sunday than Virgin Mary and Sunday school.

God: And your point is? Aren’t you the one who strives for non-judgement and unconditional love? You’ve lots of non-judgement for Buddhists, Jews, Hindus, etc. How about removing the judgement around your own faith, of ‘how’ Christians should seem to be?

Phil: (rolling eyes as God has just made a rather significant point)

God (chuckling) – You talk to Me plenty, you quietly join the midnight Christmas Eve service. You have The Great Invocation on your office wall. You feel it. You have it. Stop prevaricating.

Phil: (slightly petulant now) Okay, okay, I get it. I can’t witter about non-judgement when I’m not putting my toe in the water on this one. But You know I deal with You differently. What if I’m not, well, God enough?

God: You know Me better than that. Unconditional love is unconditional love.

Phil: You’re telling me to step up to the plate, aren’t you? Sort out my ‘baggage’ around Christianity. You know I’m going to look like a nut-job trying to explain my faith in talking to You through dreams, signs etc.

God: (drily) Solomon did OK with it.

I woke up the next day thinking, “WTF?” My husband was brought up Roman Catholic but had drifted from the church, so I decide I’d run it by him. I was sure he’d help me with a ‘get out of jail free’ card that would allow me to ignore all this oddness.

Instead, he said, “Well, Phil, Jesus did have to ask Peter three times.”

My jaw hit the floor. “You’re not helping!” I yelled. He laughed and told me to go fetch The Bible from the communal library.

I didn’t. Instead, back home, I quietly started researching. My starting point was the place where my own knowledge ended and societal pre-conceptions built up. Which took me back to 15 years old, a Church of England school, and a Divinity O-level. Plus a home life that didn’t include church, or discussion about anything religious or mystical.

So whilst I had learnt swathes of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John (even recording them onto cassette to replay at night on my Sony Walkman to deliver an A-grade in the exam), it all stopped there. The subsequent 28 years had overlaid a lovely mix of new age and eastern mysticism.

While many of the philosophies I had researched over the years held reference to God as ‘the creator and ruler of the universe and source of all moral authority; the supreme being’, only one religion included a resurrection. There was my sticking point. To get to grips with Christianity, I had to make sense of the impossible. Could a man really have come back to life? Why didn’t I recall being more astounded and moved when taught this at 15?

I could have read articles galore, downloaded YouTube videos, gone to the library for piles of books. But I had this urge to figure it out NOW, tick it off the list, and move on. The journalist in me rose to the challenge. I decided I’d pick up the phone and ask some questions of a local church. But which one?

Tony’s experience of Catholicism hadn’t left him particularly engaged. Nor did I have many happy impressions, remembering the morbid fear of discovery my friend in Ireland lived with whilst hiding his Protestant faith from his Roman Catholic flat mates.

So back to what I did know. Church of England. Which, in Australia, struck me as similar to Anglican. There just happened to be an Anglican Church just around the corner from the children’s school. Taking a deep breath, I rang the number.

It became my first discovery that God has a massive sense of humour. And is very, very smart. Had the ‘wrong’ Christian answered the phone (you know the stereotype: too much dogma, holier than thou posturing) I would have exited gracefully and taken it no further. Instead, God gave me exactly who I needed. A down-to-earth bloke with an irreverent sense of humour who not only took my mad questions on the chin, but also answered them patiently. He was then kind enough to engage in lengthy emails as I challenged, vented and searched through what I thought I knew, helping me discard the chaff whilst holding onto some wheat.

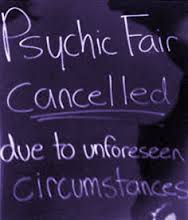

God’s humour? Well, in an odd parallel to my visiting a psychic after Mum died, the pastor – in our very first phone conversation – told me quite confidently that he knew how this all would end.

He was right too, which is a blog for another day. Smart-Alec.

In it I saw Mum running with a crowd of young children through a field of wildflowers. Very peaceful but not especially significant if you’re a skeptic reading this. Mum was wheelchair bound and disabled by her neurological sarcoid for over 20 years. My brain had been processing some pretty heavy stuff in a short amount of time. Why wouldn’t it project a feel good bit of dopamine dreaming to ease the stress?

In it I saw Mum running with a crowd of young children through a field of wildflowers. Very peaceful but not especially significant if you’re a skeptic reading this. Mum was wheelchair bound and disabled by her neurological sarcoid for over 20 years. My brain had been processing some pretty heavy stuff in a short amount of time. Why wouldn’t it project a feel good bit of dopamine dreaming to ease the stress?