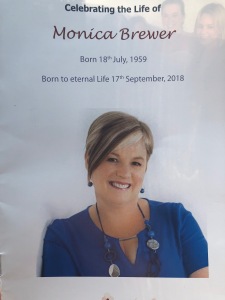

On Tuesday evening a group of my contemporaries gathered in a ‘mini-wake’ ahead of her funeral to celebrate the life of a friend, Monica Brewer. After a short, valiant journey (she didn’t like to call it a battle), she passed away early last week from a cancer that had been diagnosed a fast six months before.

On Tuesday evening a group of my contemporaries gathered in a ‘mini-wake’ ahead of her funeral to celebrate the life of a friend, Monica Brewer. After a short, valiant journey (she didn’t like to call it a battle), she passed away early last week from a cancer that had been diagnosed a fast six months before.

She is not my first friend to die of cancer. She likely won’t be my last. But I wasn’t able to meet them to celebrate on Tuesday night. I was off doing something else. Something Monica played an instrumental role in my undertaking.

I was at my Bible College class. Should I wish, and most importantly should God wish, by the end of this course (a Graduate Diploma in Divinity) I could become an ordained minister. Which I’m certain God, Jesus and Monica are now having a jolly good laugh about in heaven. I don’t think that will actually happen, my being an ordained minister. I still swear waaay too much for that. But God does have a strong sense of humour, so I’ve learnt just to wait and see.

I met Monica through the She Business group many years ago, long before I became a Christian. Christianity was not what I expected in my 40s, and it took much wrestling and cage-fighting to figure it out. One of my wrestles was being a business owner and integrating my faith and work. Soon after I was baptised in the river, I retained Monica as a business coach – totally unaware she had a Christian faith herself.

Monica mixed a no-nonsense planning approach, thanks to her background as an accountant, with a matriarchal firmness I enjoyed. As I said to her at the time, “I don’t need you to talk to me about positive thinking mindset, I need you to call me on my sh*t,” and she did.

She and I worked on developing and rebranding my communications agency. But as GJ&HS swept relentlessly through my life, she could tell my heart wasn’t in it. I wanted a Kingdom-business but I was a new Christian still figuring out the Kingdom for me, let alone a business. It’s like I didn’t know enough about my own faith then to work it all out.

One day – after one of those dangerous crazy prayers – an executive role in an international not-for-profit Christian mission presented itself.

I remember turning up to my next planning meeting with Monica, totally conflicted. We had spent months, after all, planning and structuring this new agency. I told her about the prayer, and what had happened 24 hours later. “I just got goose bumps,” she told me. “Follow this. The agency will always be there for you to pick up. God will do the rest.”

Of course, she was right. He did. With spectacular results. From her encouraging me to walk through that first door, I now find myself studying, writing and preaching. Plus a new opportunity that saw me launch the Ministry of Sex. Yes, you read that right. And no, I’m not administering that sort of pastoral care. Everyone calm down.

The agency has also been prepared for me to pick it up again. Whilst working in the mission, I ran it remotely with an awesome team. Was it a juggle? Yes. Am I ready to focus on it fully, now? Yes.

Monica was part of that too. Three years ago she helped show me how to run a Kingdom business that integrated my faith – I just wasn’t sufficiently mature in my faith to recognise it at the time. During our meetings, our laptops open at her wooden dining table, an overseas visiting pastor (staying with the family as he studied at Bible college) would wander in and out. There was my Kingdom business model. Love God, love what you do in business, serve where you can and do it for His glory. He looks after the rest.

Today was her funeral. I love that they read Proverbs 31, as it encapsulates her perfectly. A woman of Godly character, in successful business, full of energy, with strength in her arms. Facing a cancer diagnosis that she called a gift from God, her faith assured her. I don’t doubt she was clothed with strength and dignity – and she may not have been laughing at the days to come, as the Psalmist writes, but she would have been fearless.

Thanks Monica. The biggest blessing is knowing I get to spend eternity with you in heaven. Dancing, just as we all did leaving the church today, just as you asked.

God bless.